One goal of this trip had been to research the St. Lawrence Seaway for a future novel (a sequel to Breaking Anchor). From Mary Ann’s perspective it was an opportunity to go whale watching.

One goal of this trip had been to research the St. Lawrence Seaway for a future novel (a sequel to Breaking Anchor). From Mary Ann’s perspective it was an opportunity to go whale watching.

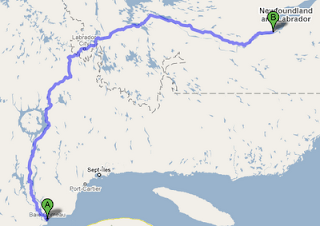

But after seeing Minke and Humpbacks and the others, we headed north inland from Baie-Comeau up the Labrador highway. From our limited Québec map, it looked like very few towns along this route, so resolved to fill the gas tank at every opportunity, we chugged along, seeing evidences of a massive hydro electric project all the way up the Manicouagan river. A series of five dams named Manic 1 through 5 are the sources for the paths of giant transmission towers we’d been seeing all along the highway.

Looking at the map, in addition to the lure of unknown Labrador was the bulls-eye emblem of the Manicouagan reservoir. This had to be one of the largest meteor craters on the planet, and the highway drove right through it. I’m a sucker for meteors. I have two iron fragments in my desk at home.

But the road was long and I hadn’t started until after the whale boat tour, so near sunset we arrived at Manic Cinq and it’s pleasant oasis of gas station, restaurant and motel rooms. It was the last Internet connection we had for a few days. Rogers cellular had dropped off as we left the St. Lawrence. I started building up tweets on my iPhone to send later.

The Manicouagan reservoir was more than just a round lake with a round island in the middle. The impact, some 214 million years ago, had left a 62 mile wide splash crater in the form of mountans that ringed the area we were diving through. Just like the Charlevoix crater down on the St. Lawrence, this meant sifting down to take the 12-19% grades. And by this time the pavement was behind us. A gravel highway is quite drivable, but it’s something like driving on ice. You have much less control than it seems, especially on curves and when stopping. I can understand why moose on the road at night can be lethal.

The Manicouagan reservoir was more than just a round lake with a round island in the middle. The impact, some 214 million years ago, had left a 62 mile wide splash crater in the form of mountans that ringed the area we were diving through. Just like the Charlevoix crater down on the St. Lawrence, this meant sifting down to take the 12-19% grades. And by this time the pavement was behind us. A gravel highway is quite drivable, but it’s something like driving on ice. You have much less control than it seems, especially on curves and when stopping. I can understand why moose on the road at night can be lethal.

The map showed a town named Gagnon north of the crater, but pavement returned, complete with sidewalks and curbs, but there were no buildings. The entire place had been … removed. Pavement continued up for several miles until we reached what appeared to be an abandoned mine at Fire Lake. The rail spur onto the mine was rust covered and unused.

Shortly we reached Labrador and the active iron mines that powered the economies of Fermont and Labrador City were massive, disassembling this mountain and building another, giant truckload by giant truckload.

Past Labrador City, highway 500 stretched ahead, with only two cities on it’s 500+ km way across the full width of Labrador; Churchill Falls, and Happy Valley-Goose Bay. A gravel highway, raised five to eight feet above the terrain the whole way. This is relatively new construction because in several places I saw the old route 500, a single lane dirt road twisting its way around the bogs and across the creeks. And if you think hundreds of kilometers of raised roadbed would take a lot of crushed rock, you’re right. Every so often, there would be an acre’s worth of quarry, carved from the granite.

Past Labrador City, highway 500 stretched ahead, with only two cities on it’s 500+ km way across the full width of Labrador; Churchill Falls, and Happy Valley-Goose Bay. A gravel highway, raised five to eight feet above the terrain the whole way. This is relatively new construction because in several places I saw the old route 500, a single lane dirt road twisting its way around the bogs and across the creeks. And if you think hundreds of kilometers of raised roadbed would take a lot of crushed rock, you’re right. Every so often, there would be an acre’s worth of quarry, carved from the granite.

We stopped for the night at Churchill Falls, a company town dedicated to the hydro power plant capable of producing more than 5000 megawatts by channeling water from the Smallwood Reservour? into the deep canyon holding the Churchill river. It was a fascinating little town and don’t be surprised if it shows up in one of my novels.

We stopped for the night at Churchill Falls, a company town dedicated to the hydro power plant capable of producing more than 5000 megawatts by channeling water from the Smallwood Reservour? into the deep canyon holding the Churchill river. It was a fascinating little town and don’t be surprised if it shows up in one of my novels.

Sunday, we completed the last leg of highway 500 and came down off the plateau of shallow lakes and bogs into the glacier carved wide valley that was home to Happy Valley and Goose Bay.